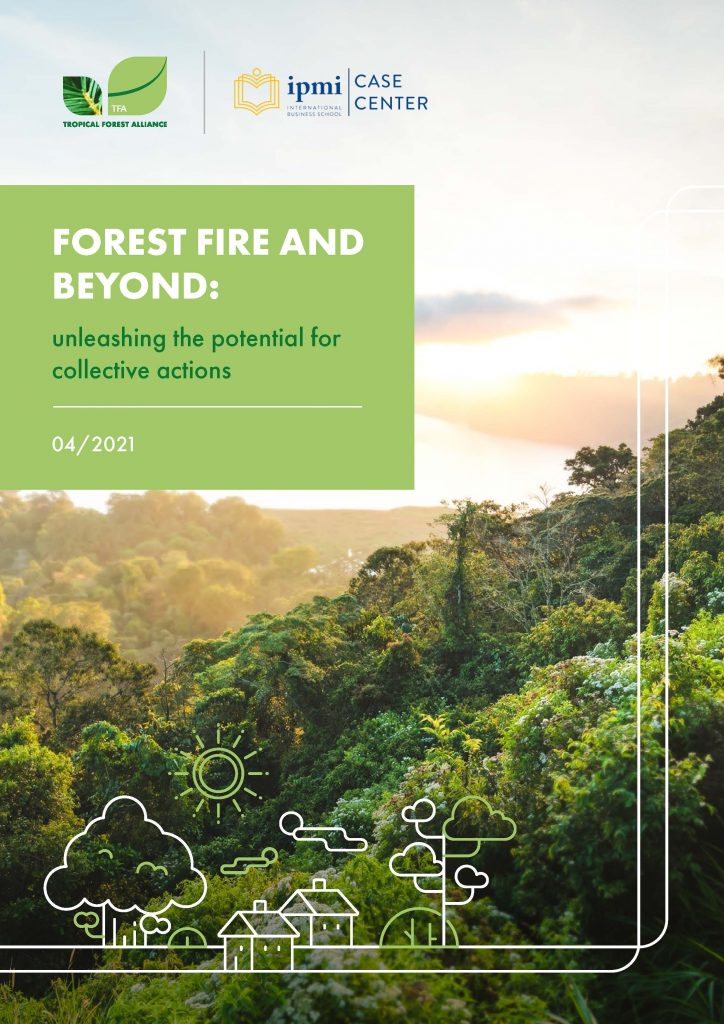

The 2015 mega-fires that raged across the forests and peatlands of Sumatra were the worst in the history of Indonesia, spreading smoke and haze throughout Southeast Asia. In that same year, APRIL (Asia Pacific Resources International) Group, the second-largest pulp and paper company in Indonesia and one of the largest in the world, was experiencing positive results from its Fire Free Village Program pilot: a community-based program to eliminate the use of fire in village communities surrounding APRIL’s operations.

The Fire Free Village Program (FFVP) program, piloted in 2014 and formally launched in 2015, is a community engagement program that aims to understand the root causes of forest fires and implement sustainable ways to reduce or eliminate them in the communities neighboring the company’s forestry operations and beyond.

By 2018, the program had expanded to include 77 village communities in Riau Province, Sumatra.

Results were immediately positive. Four out of the nine villages participating in the pilot program achieved a fire-free record. Two villages had less than 2 hectares of area impacted by fire during the program period, while three villages still had more than 2 hectares impacted by fire. Overall, within two years of the program, the nine villages were able to reduce fires in their respective areas by 95% (Tribolet, 2020).

Shortly afterwards, in 2016, the Fire Free Alliance (FFA) was formed, a voluntary multi-stakeholder group including forestry and agriculture companies and civil society organisations set up to address the persistent issue of fire and smoke haze arising from the burning of land in Indonesia. While fires and smoke haze have declined in intensity in recent years through government-led national fire prevention efforts, the Indonesian government was determined to find a permanent solution to the annual recurring fires. The FFVP and the FFA support the government’s fire prevention efforts in Sumatra and right across Indonesia.